Guest Blog by Hayley Franz, URI Marine Affairs student

Hayley volunteering at one of Eating with the Ecosystem’s Scales & Tales Food Boat events this fall.

On November 29, 2018 I had the pleasure of listening to two graduate students talk about their studies at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography. Both women helped fill a complete picture of what is going on in the Narragansett Bay in regards to the food chain and climate change.

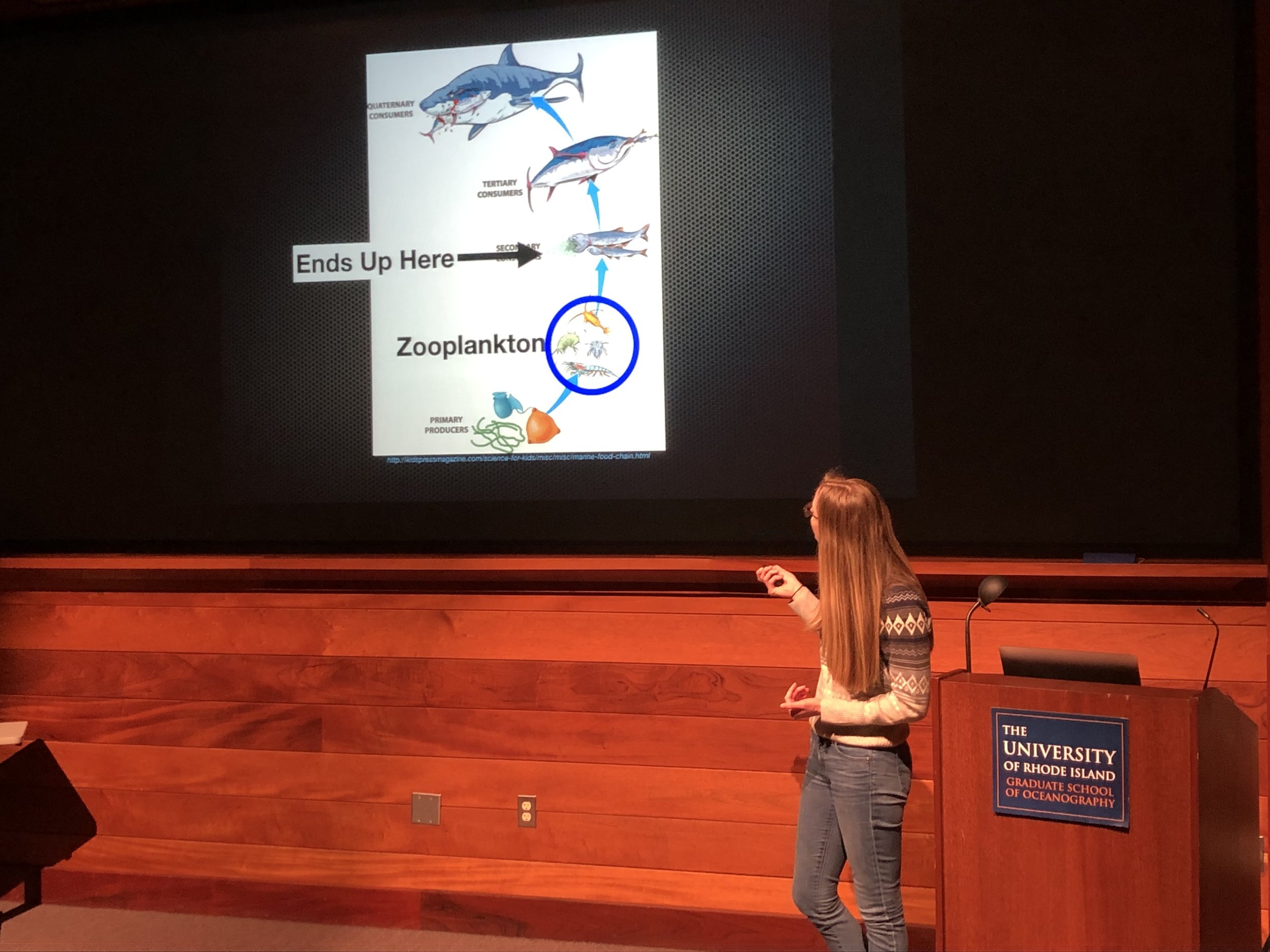

Nicole Flecchia delivered the first presentation. Her studies focus on small-scale food webs. She looks directly at the primary producers (organisms such as phytoplankton that make their own food) and consumers. Her presentation concentrated on the chain of nutrients to phytoplankton and then to zooplankton. Flecchia started her presentation talking about the amount of nitrogen in the bay, a key nutrient needed to feed phytoplankton. Phytoplankton, like their terrestrial plant relatives, require nutrients such as nitrogen to grow. The phytoplankton are then consumed by zooplankton (the animal constituent of plankton, which consists mainly of small crustaceans and fish larvae). This is a key step in the food chain, as zooplankton are an important food source for many Narragansett Bay fish. Additionally, many of the zooplankton that are not eaten then grow up to become some of our favorite seafood species. Flecchia noted that while nutrients such as nitrogen in the bay are important, when there are too many nutrients in the bay it can lead to fish kills like the one from 2003. To understand the chain in a simple way, more nutrients leads to larger phytoplankton blooms. When the phytoplankton die they begin to decompose, a process that uses oxygen. When the bloom is big enough, it can use too much oxygen, killing the fish left in the oxygen depleted waters.

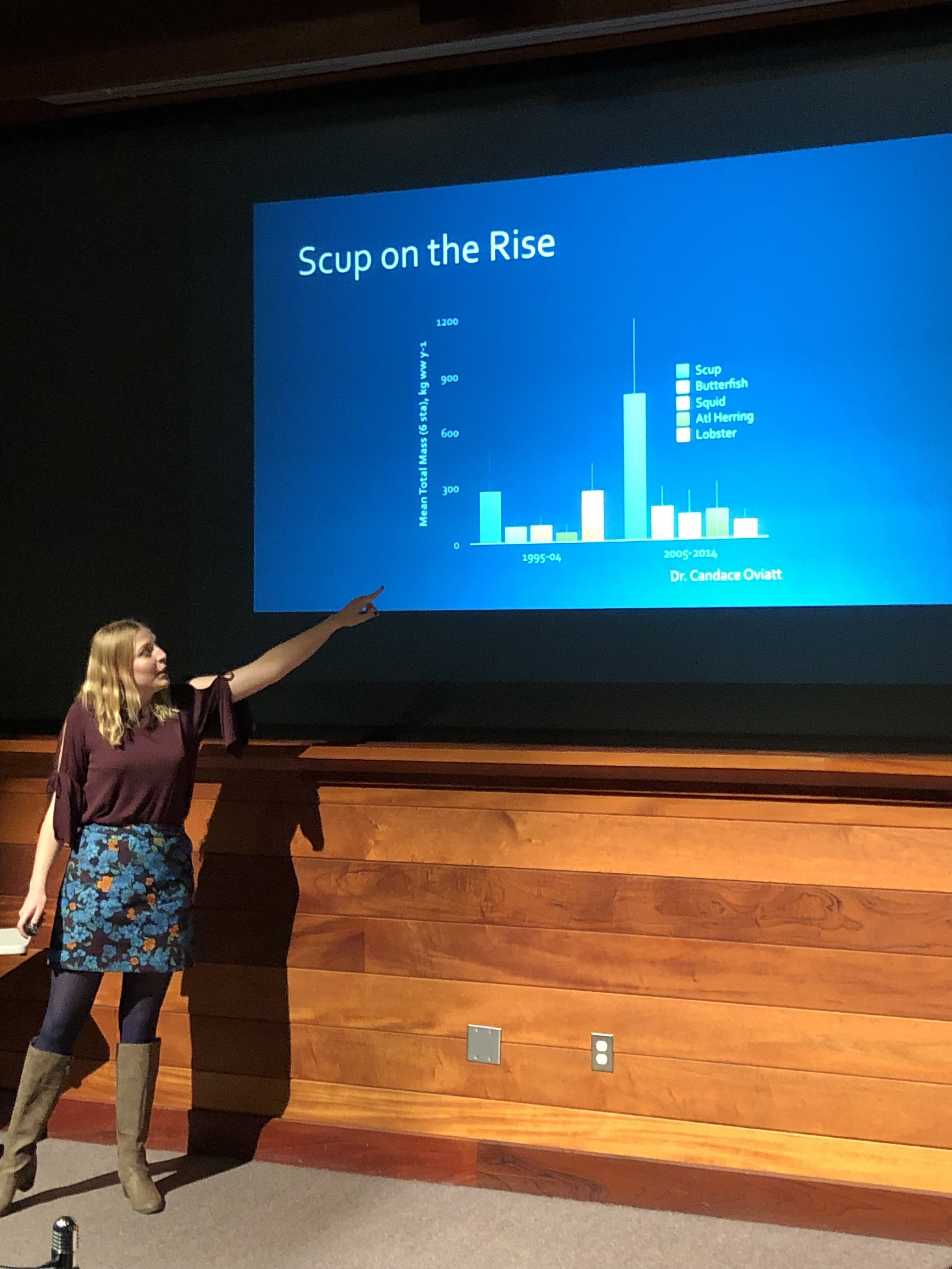

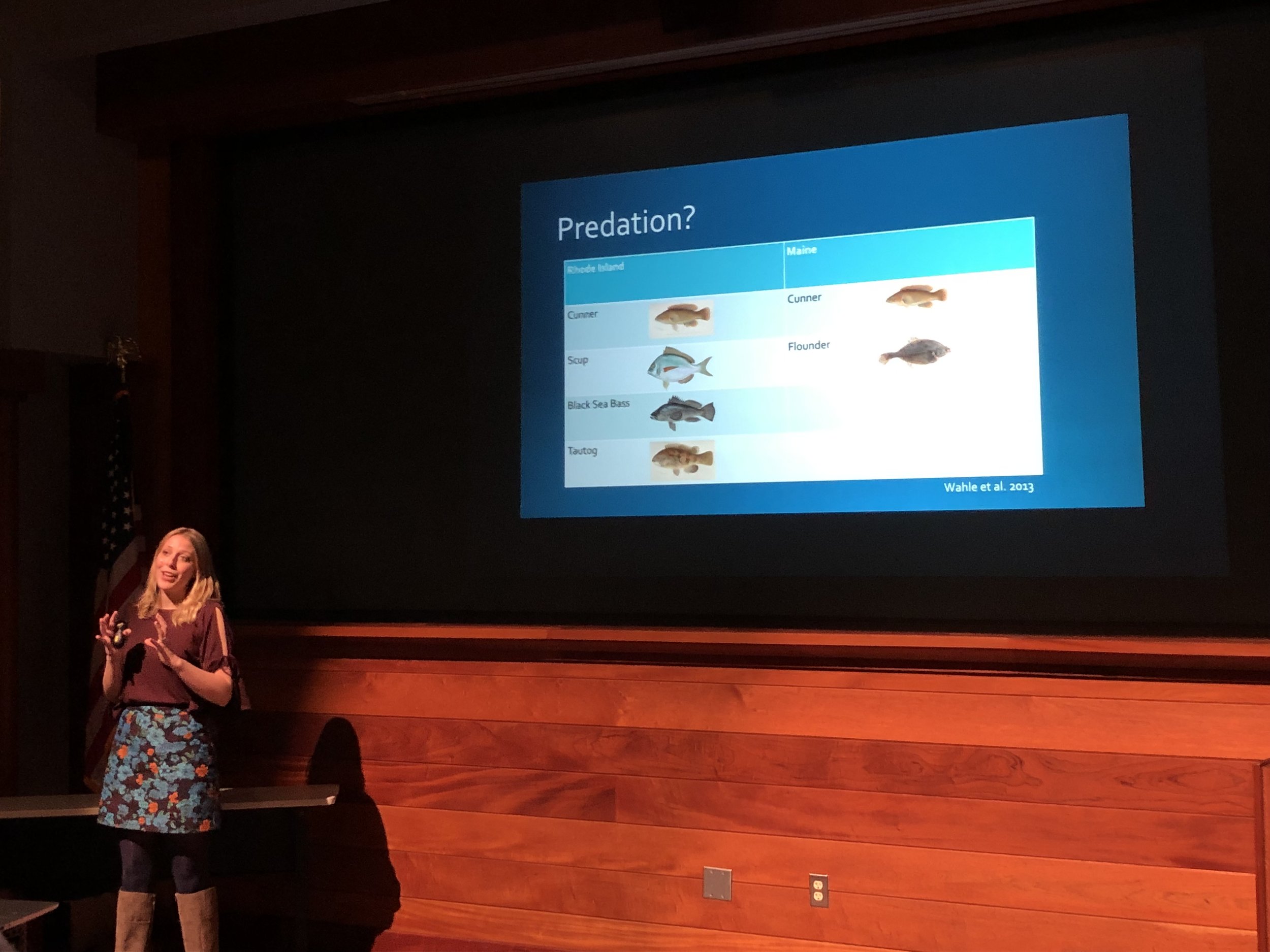

The second presenter was Kristin Huizenga and her presentation was focused on fish, lobster, and climate change. Many of us love lobster but did you know Rhode Island used to have a much larger fishery for lobsters? Huizenga talked about how the water in Narragansett Bay has become warmer, causing Rhode Island’s lobster populations to continuously decline. Lobsters prefer colder water temperatures. A normal lobster nursery is well below 20°C. In the last 50 years the Narragansett Bay has warmed by about 1.5°C lobster populations have been moving north towards Maine and Canada. By 2050 the bay is predicted to be too warm for lobsters to even survive. Warmer water temperatures are not only making the bay too warm for lobsters but are also bringing increased predators. Fish such as scup and black sea bass eat juvenile lobsters and actually prefer these warmer water temperatures. As the bay has warmed, we have seen an increase in both of these lobster predator species.

So you must be thinking this is a lot of information. What do I do with it? What does this mean for the seafood we love? Well, I’ll tell you. Try to regulate what nutrients aka fertilizers you use on your lawns. This can limit the nutrients going into the bay, helping to maintain healthy water quality and save ecosystems. If you love lobster and other local seafood species that prefer colder water temperatures, such as winter flounder, you can also try really hard to lower your carbon footprint. And one of my favorite ways that you can try to save lobster populations in Narragansett Bay is to eat some of the predator species such as scup and black sea bass. These fish are abundant and tasty! If you as a consumer go into your local fish market or grocery store and ask for scup and black sea bass it will help to create more markets for these fish and hopefully give young lobsters a better chance to reach maturity, therefore hopefully helping the lobster population!